Improvements to Lock-Free Transactional Transformation

Musings permalink

Recently, I went to CppCon, where I saw tons of great talks and had many insightful discussions. The community is brilliant, and the fields they come from are diverse. I was there with my team to present our lab's latest research work at an industry-centric conference. More specifically, I co-presented on our lab's use of persistent memory to augment concurrent data structures. One of the papers we presented was PETRA: Persistent Transactional Non-Blocking Linked Data Structures. This work augments one of our lab's earlier papers, Lock-Free Transactional Transformation for Linked Data Structures, more commonly called LFTT, by leveraging its existing transaction descriptors for use as persistent logs. This presentation brought the core LFTT design back into my thoughts.

LFTT permalink

LFTT was one of the earliest projects I work with in my lab. It was the foundation of what I built for my Senior Design project in my undergraduate program, a project which ultimately led to my pursuit of a Ph.D.

LFTT is a static transactional framework. Unlike traditional works, where transactions conflict on low-level reads and writes at individual memory locations, LFTT only considers high-level semantic conflicts. In other words, we don't care what memory locations a transaction reads from or writes to; we care only about which nodes we insert, delete, or find. This approach often results in a significant performance improvement over traditional methods. For instance, a linked list insertion in a transaction must add all traversed links to the read set when considering low-level reads. These can conflict with removals of any of the traversed nodes in traditional frameworks. LFTT, on the other hand, only needs to consider the inserted node itself for potential conflicts. Reduced conflicts mean increased parallelism and reduced time bottlenecked on conflict resolution. By building LFTT on top of existing lock-free node-based lists, we get consistency and progress for free while adding transactional correctness. LFTT is a great solution, but it has several limitations that our lab has slowly worked to overcome and improve upon.

Improvements permalink

Some members of my team have added support for dynamic transactions, where the operations that need to occur are not known until after the transaction has started. This allows for functionality such as conditional logic, where the result of one operation determines which operations happen next within a transaction. This paper also added wait-free guarantees (over the lock-freedom used in the original paper) and support for transactions involving multiple LFTT data structures at once.

My Improvements permalink

During most of 2019, I spent my time thinking about how to augment LFTT further when I applied the design to a vector data structure, a type of resizable array, in my paper, Lock-free transactional vector. By this point, now four years since the original LFTT publication, we were concerned that reviewers would complain about this work appearing to be a simple incremental improvement over LFTT. As a result, I feel that my final publication underplayed the significance of the improvements I made to LFTT, which were numerous. Here is a list of LFTT limitations, all resolved in my paper:

- LFTT only works with set-based data structures

- LFTT only works on node-based data structures

- LFTT will always write and can conflict, even for read-only transactions

- LFTT conflict resolution is prone to a cyclic dependency

- LFTT suffers from the ABA problem

Now I will discuss how I addressed each of these issues.

LFTT only works with set-based data structures permalink

LFTT was designed only to work on ordered sets, containers of elements that are either present or absent (just like mathematical sets). In a vector, each element is associated with an index. This means that each of our items must track both an index and a value, not just presence. Supporting this would also be useful for key-value data structures. I added support for this in the transactional vector.

In a transactional framework, transactions must be "atomic", which is a fancy way of saying either the whole transaction appears to succeed in an instant or fails and never takes effect. Thus, any work done before failure must be reverted. Properly maintaining the right value to pair with a key in LFTT is a surprisingly tricky process, as old values must be properly maintained to logically roll back failed transactions.

LFTT only works on node-based data structures permalink

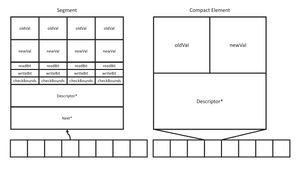

LFTT was designed to work only on node-based data structures, such as linked lists, skip lists, trees, tries, MDLists etc. This is clearly incompatible with the array-based design of the vector. One may at first consider making the vector node-based, but this would defeat the entire design advantage of the vector, namely the contiguous storage guarantees. Instead, I extended the design to apply to array-based data structures. This was tricky, as I could not rely on RCU mechanisms present on node-based structures. I accomplished this via two approaches: the compact vector limits the size of each vector index to fit in a 128-bit atomic, and the segmented vector provides updates via an atomic pointer to the value. Elements are handled in segments the size of a cache line, to maximize cache locality, meaning I had to support layering. Partial layer updates meant that some historic layers had to be preserved in a chain of updates.

LFTT will always write and can conflict, even for read-only transactions permalink

LFTT maintains transaction state using a transaction descriptor. This descriptor maintains a list of operations, and any operation that has physically occurred points back to its own descriptor. This enables other threads to identify conflicting transactions and help them complete. Because this is the core mechanism for conflict detection, a transaction descriptor must be allocated even for read-only transactions. From there, each element read must have its transaction descriptor pointer updated to point to its latest transaction descriptor. Furthermore, these transactions always conflict with any overlapping transactions. This is bad because, in traditional transaction frameworks based on low-level reads and writes, a read never conflicts with another read, but in LFTT they do.

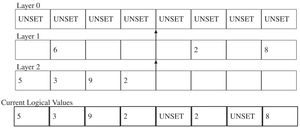

When applying my layering trick to support array-based transactions, I noticed that the chain of updates, without memory reclamation or consolidation, provides a comprehensive history of all previous values. This provides an interesting opportunity for read-only transactions. I can linearize at the very start of any read-only transaction and, because historic values are present, I can read whatever value was present at the start of the transaction, while totally ignoring any other transactions as they update the values. This required adding a counter to version each transaction, to identify the state of the vector at the start of the read-only transaction and know how far back in time to read values. This design comes at the cost of space, as historic records must be preserved for these operations, and some amount of synchronization overhead from the shared atomic counter, but it completely eliminates conflicts for read-only transactions.

LFTT conflict resolution is prone to a cyclic dependency permalink

LFTT's original version was lock-free. It could not guarantee wait-freedom because the conflict resolution algorithm was prone to a cyclic dependency, where the only way to break the cycle was to abort at least one of the offending transactions. This can occur, for instance, if one transaction is trying to insert nodes for 1 and 2, in that order, and another is trying to insert for nodes 2 and 1, in that order. The first will physically insert 1 and the second will physically insert 2. Now the first will try to physically insert at 2 and see the other transaction has claimed this spot, so it will try to help that other transaction complete. Likewise, the other transaction is trying to physically insert a 1 and will see the first transaction already claimed that spot, then try to help it complete. This causes an endless helping dependency, which the original paper breaks up by tracking if recursive helping adds the same transaction to the help stack multiple times and then killing one of the transactions. As mentioned before, one of my team's previous papers addressed this problem, but I found what I consider a simpler and more elegant solution.

In my solution, I leverage the static transactions present in LFTT. When a transaction is static, we know ahead of time the complete list of operations a transaction wants to perform. What this means is that we can apply a deterministic order of operations for all transactions. Simply put, we can perform operations in sorted order, from low to high index/value. This will make cyclic dependencies impossible, and since transactions are an all-or-nothing matter, it doesn't matter which order we perform operations at the semantic level, as no one will see the intermediate state externally. If we apply this deterministic approach to our previous example, both transactions would try to insert 1 first. One will succeed and try to insert 2. The other will see the conflict on 1 and help the successful transaction insert its 2.

LFTT suffers from the ABA problem permalink

Another lab interested in our work identified a concurrency bug in the original design of LFTT. If a thread, T1, becomes idle just before adding a new node to the list, then a second thread, T2, can help and commit. However, if another transaction removes that node before T1 resumes, T1 could actually succeed in inserting the node again, after its own transaction has already committed. This is an occurrence of the ABA problem. My vector design avoided this issue, as it does not need to deal with node reinsertion. A proper fix to the node-based design would add a counter in the unused bits of each node pointer, to help ensure pointer uniqueness.

Conclusions permalink

Ultimately, I've been thinking of LFTT again because of PETRA. PETRA was being designed while I was working on my transactional vector. This means that several of these design enhancements didn't make their way to PETRA in time for its publication. Fortunately, these enhancements have been published, meaning anyone attempting to use PETRA could foreseeably implement these improvements there. I hope this blog post is useful for anyone wanting to avoid the same pitfalls in the future.